One day in 2010, I flipped through the latest issue of National Geographic and counted how many women and how many men were mentioned by name. It was actually an article about women in a particular country that sparked my curiosity. The unusually many women in that article (it turned out to be 8 women and 4 men) stood out in contrast with the rest of the magazine. The other feature articles (none of which were purportedly about men) mentioned in total 54 men and 12 women. I wrote a letter to the editors of National Geographic, thinking maybe they didn’t realize their numbers were so out of whack. They didn’t reply.

I started to wonder how National Geographic compared to other magazines. I was most interested in magazines that, like National Geographic, focus a lot on science and technology. My friends Anne, Debbie, Melissa, and Steve helpfully recommended magazines and even gave me their old copies. (Thanks!)

I counted women and men in a bunch of magazine issues, made some graphs… and then got stuck. I wanted to tell people about these numbers, but how could I explain them? Did they actually show anything that wasn’t already obvious? Could I draw any conclusions from them, or would I just be holding them up as justification of my own presuppositions? Was this small sample really representative? Would the numbers be different in more recent issues?

Over seven years later… I still have no coherent explanation. Instead, I offer more of a scrapbook. My counts of women and men (in sections labeled “humble data”) are interspersed with a collection of quotes and thoughts. All of this probably raises more questions than it answers.

Table of Contents

- Popsci.com image

- Deviation from the ideal male or female

- Third, fourth, fifth, or more genders

- Is it a boy or a girl?

- How many women work in science/technology?

- Patterns in higher-dimensional space

- Humble data — Women written about in science/technology magazines

- Demographic trap

- Humble data — Women writing in science/technology magazines

- More women, less pay

- Science/technology compared to other industries

- Humble data — Women reading science/technology magazines

- Circulation is replaced by reach and engagement

- Defining what is important

- Her soft features belying her outsize thesis

- Pop-cultural imperialist anthropology

- Humble data — Advertising in science/technology magazines

- How more subtly to control the press

- Advertising in science/technology magazines for kids

- Humanity would be extinguished

1. Popsci.com image

The image at the top of this post came from the media kit for the Popular Science website. The media kit is a brochure that tells potential advertisers about the magazine (or in this case the magazine’s website), including ad prices, circulation, and reader demographics. This image describes readers of the site as (in this order): “male”, “wealthy and educated”, “tech-savvy”, “hungry for knowledge”, and “innovators”. The same media kit said that the fraction of women among visitors to their site was about 1/3.

I downloaded the image in 2011 or 2012. It’s no longer part of the media kit.

2. Deviation from the ideal male or female

From “How sexually dimorphic are we?” by Melanie Blackless, Anthony Charuvastra, Amanda Derryck, Anne Fausto‐Sterling, Karl Lauzanne, and Ellen Lee (2000), as quoted by Hida of Intersex Campaign for Equality:

The belief that Homo sapiens is absolutely dimorphic with the respect to sex chromosome composition, gonadal structure, hormone levels, and the structure of the internal genital duct systems and external genitalia, derives from the platonic ideal that for each sex there is a single, universally correct developmental pathway and outcome. We surveyed the medical literature from 1955 to the present for studies of the frequency of deviation from the ideal male or female. We conclude that this frequency may be as high as 2% of live births. The frequency of individuals receiving “corrective” genital surgery, however, probably runs between 1 and 2 per 1,000 live births (0.1–0.2%).

3. Third, fourth, fifth, or more genders

From “A Map of Gender-Diverse Cultures” shared by Independent Lens in conjunction with the film Kumu Hina:

On nearly every continent, and for all of recorded history, thriving cultures have recognized, revered, and integrated more than two genders. Terms such as “transgender” and “gay” are strictly new constructs that assume three things: that there are only two sexes (male/female), as many as two sexualities (gay/straight), and only two genders (man/woman).

Yet hundreds of distinct societies around the globe have their own long-established traditions for third, fourth, fifth, or more genders. The subject of Two Spirits, Fred Martinez, for example, was not a boy who wanted to be a girl, but both a boy and a girl — an identity his Navajo culture recognized and revered as nádleehí. Meanwhile, Hina of Kumu Hina is part of a native Hawaiian culture that has traditionally revered and respected mahu, those who embody both male and female spirit.

Most Western societies have no direct correlation for this tradition, nor for the many other communities without strict either/or conceptions of sex, sexuality, and gender. Worldwide, the sheer variety of gender expression is almost limitless.

4. Is it a boy or a girl?

Here in the United States, despite strict taboos against pedophilia, people are weirdly obsessed with the genitalia of babies. The question on everyone’s mind is (euphemistically) “Is it a boy or a girl?”

This doesn’t just determine the color of the cake frosting at the prenatal gender reveal party. Whatever the doctor writes on your birth certificate, that is the gender role you’re assigned to for the rest of your life, unless you go to great lengths to change it. Most people are fine with this. Some of us aren’t.

I suppose there’s some complex feedback loop of nature and nurture, of social interactions, hormones, brain structure, experiences, personality, body shape, and culture (that which provides ready-made answers to the problems of life) that leads a person to feel at home with the statement “I am a girl/woman” or “I am a boy/man” or both or neither.

My own birth certificate says “female”. I think I crossed the line from “tomboy” to “gender non-binary” when, as an adult, I started shopping for clothes exclusively in the men’s department. My gender expression went from harmless to making people uncomfortable.

I crossed another line when I started asking people to refer to me by the pronouns “they/them” instead of “she/her” (because the way you talk about someone influences the way you think about them, and I’d like people to think about me accurately). Now that really makes people uncomfortable.

Had I started collecting data on gender in science/technology magazines now instead of several years ago, I probably would have done it differently. I wouldn’t have been so quick to categorize people as female or male based on their name, or even the pronoun with which the writer referred to them. Maybe I would have said, “To heck with this. Why should I care if women are merely underrepresented in science/technology magazines when gender non-binary people are completely invisible?”

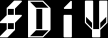

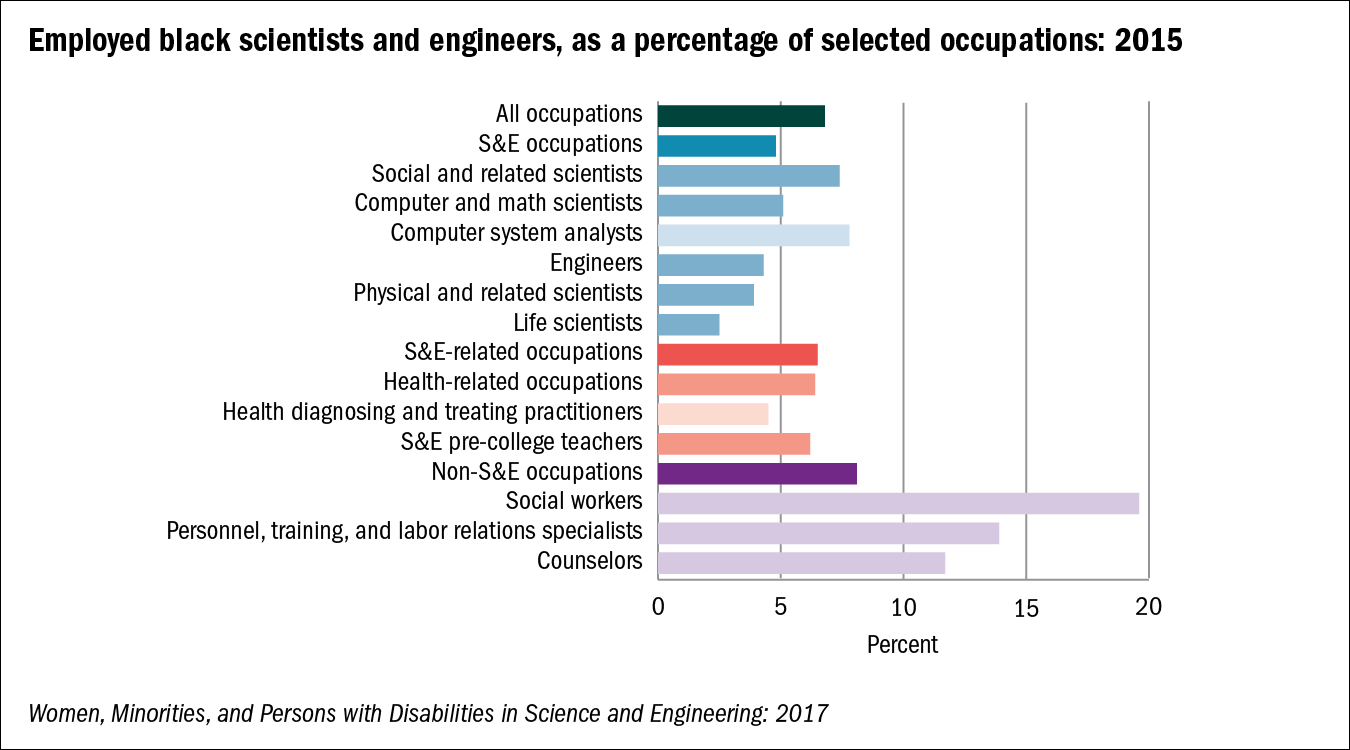

5. How many women work in science/technology?

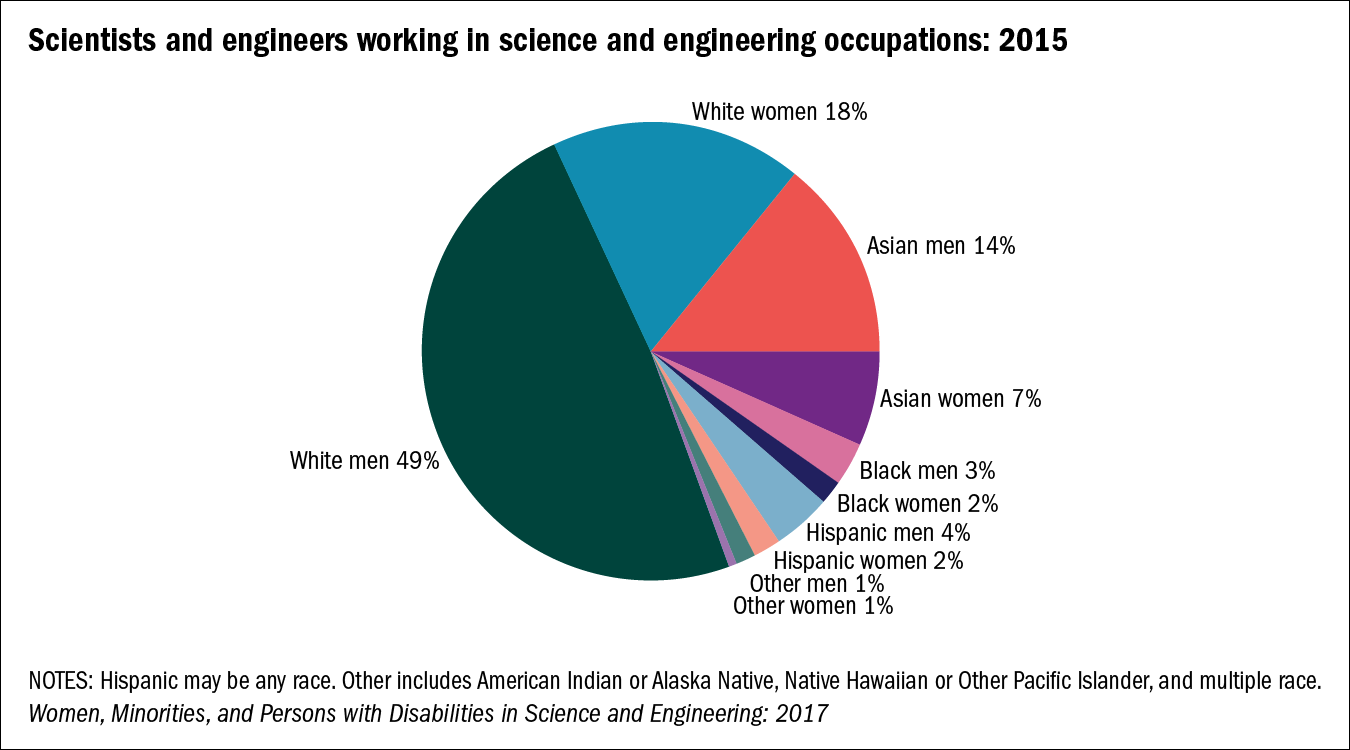

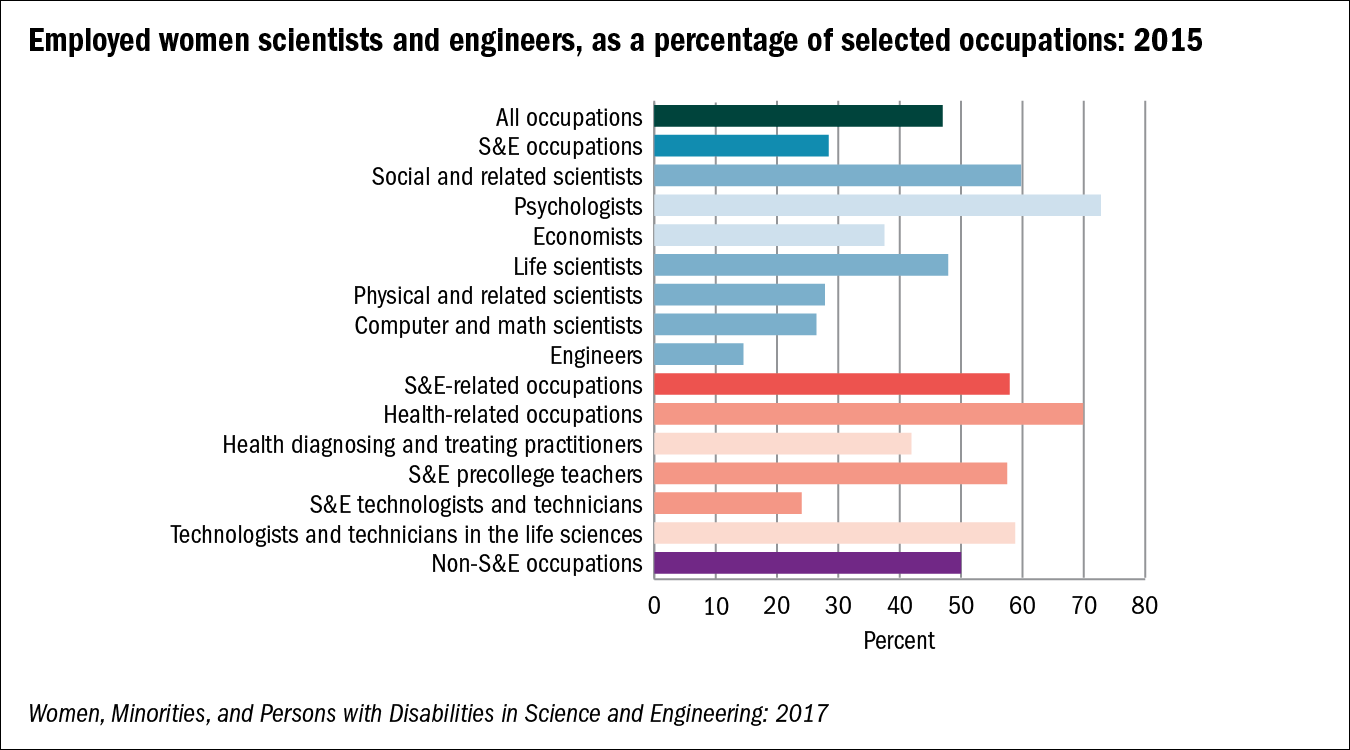

In the United States, of employed scientists and engineers, women make up about 29%.

The graphs below are from the National Science Foundation.

The percentage of women differs widely by occupation. In engineering and some of the so-called hard sciences, women are underrepresented. The life sciences have just about reached equal numbers of women and men. Some of the so-called soft sciences have overshot. Social and related scientists are 60% women, with the subdiscipline of psychology at 73% women.

I was surprised to see that you can’t simply rank the science and engineering occupations from most to least diverse. Social and related sciences do have the most women, the most blacks, and the most Hispanics. (Remember: women includes women of various races and ethnicities, blacks includes people of various ethnicities and genders, and Hispanics includes people of various races and genders.) But the occupation with the least women — engineers — is the second highest for Hispanics and in the middle for blacks.

Within a field of science/technology, there are clusters of men in some subfields and clusters of women in others. For example, among scholarly articles published between 1990 and 2010 in the field of sociology, only 36% of authors were women in the subfield of criminology, while 62% of authors were women in the study of aging parents. (Robin Wilson of The Chronicle of Higher Education (2012) reporting on research by Jennifer Jacquet, Carl T. Bergstrom, and Jevin West)

As of 2007, of all scientific researchers worldwide, women made up an estimated 29%. In some countries — including Brazil, Cuba, Argentina, Serbia, Latvia, Thailand, and Kazakhstan — women comprised more than half of scientific researchers. (UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

The percentage of female STEM graduates is negatively correlated with a country’s Global Gender Gap Index (Olga Khazan in The Atlantic (2018), reporting on research by Gijsbert Stoet and David Geary). This is the opposite of what I would have expected. Shouldn’t countries with greater opportunities for women have more women in STEM? The authors of the study “posit that this is because the countries that empower women also empower them, indirectly, to pick whatever career they’d enjoy most and be best at.” Maybe… But do young women, or young people of any gender, and their parents and guidance counselors and such, understand enough about the work people do in STEM to really know what they would enjoy most and be best at?

6. Patterns in higher-dimensional space

From Warped Passages by Lisa Randall (2005):

You might be intrigued to know that there could be a vestige of extra dimensions hidden in your kitchen cabinet — on a nonstick frying pan coated with quasicrystals. Quasicrystals are fascinating structures whose underlying order is revealed only with extra dimensions. A crystal is a highly symmetric latticework of atoms and molecules with one basic element repeated many times. In three dimensions we know what structures crystals can form, and which patterns are possible. However, the arrangement of atoms and molecules in quasicrystals does not conform to any of these patterns.

An example of a quasicrystalline pattern is shown in Figure 2. It lacks the precise regularity you would see in a true crystal, which would look more like the kind of grid you would see on a piece of graph paper. The most elegant way of explaining the pattern of molecules in these strange materials is with a projection — a sort of three-dimensional shadow — of a higher-dimensional crystalline pattern, which reveals the symmetry of the pattern in a higher-dimensional space.

A way of visualizing what intersectional feminists have been saying all along: To understand phenomena involving gender, you have to look at more dimensions than just gender.

7. Humble data — Women written about in science/technology magazines

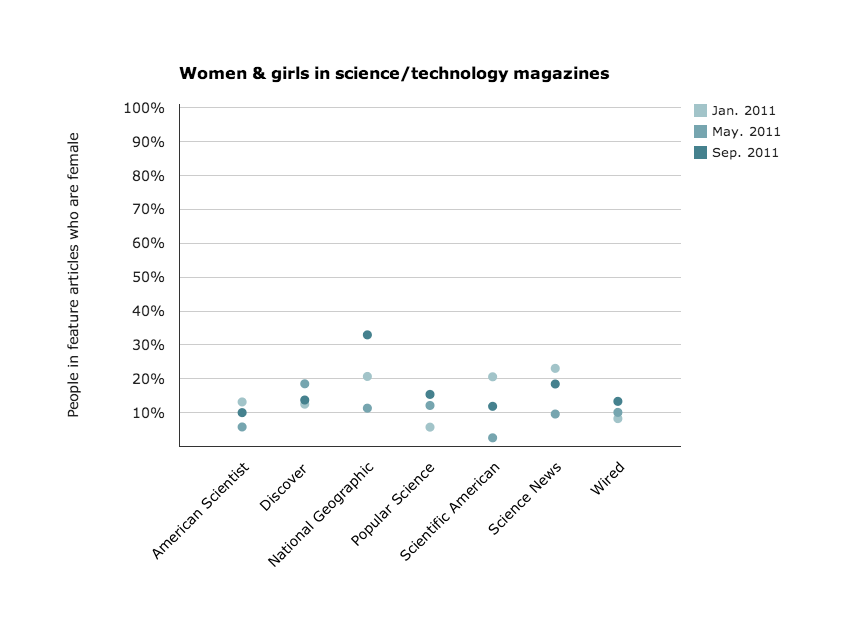

When I decided to count the mentions of women and men in science magazines, I somewhat arbitrarily picked 7 magazines that were available at my local libraries and that covered science/technology: American Scientist, Discover, National Geographic, Popular Science, Scientific American, Science News, and Wired.

I soon realized that it takes quite a while to go through an entire issue counting people. So I ended up collecting data only from the January, May, and September 2011 issues of each magazine (print edition), and only from feature articles.

(For magazines that publish an issue more or less often than once a month, I looked at whichever issue(s) had January, May, or September in their date: for example, the September-October issue of American Scientist and both the September 10 and September 24 issues of Science News.)

(It was sometimes hard to tell if an article should count as a feature article or not. Based on the length of the article and where in the magazine it was located, I took my best guess.)

I classified each person as “female”, “male”, or “unknown”, based on pronouns used in the article, photos accompanying the article, the person’s name, and/or information about the person found by a web search. The vast majority were classified as either “female” or “male”.

Of the people mentioned by name in feature articles, here are the numbers of women and girls:

The issue with the smallest percentage of women was the May 2011 Scentific American, with 3% women. In its coverage of biology, medicine, psychology, math, astronomy, and energy technology, it mentioned 74 men, 2 women, and 2 people whose gender I couldn’t classify.

The issue with the greatest percentage of women was the September 2011 National Geographic, with 33%. Most of them came from an article about fertility rates in Brazil, which named 25 women and girls, 8 men and boys, and 2 people whose gender I couldn’t classify. However, in the same issue, 3 of the other 5 feature articles mentioned no women at all.

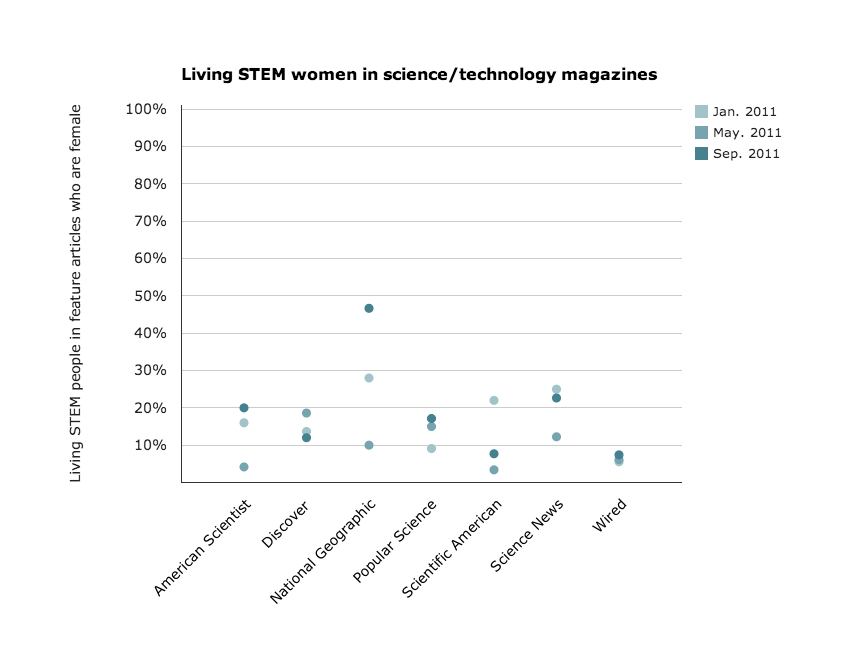

Even if the genders of people mentioned in these magazines weren’t in proportion to the general population, I was curious if the genders of the people consulted for their expertise in STEM would be proportionate to the genders of people working in STEM. I decided to count the people mentioned by name who worked in STEM and who were living at the time the article was written. This would filter out some of the anti-female bias that science writers have no control over: women’s almost blanket prohibition from working in science/technology in past centuries, gender discrimination in other areas such as politics.

(Some people were hard to classify as STEM or not. If I thought that their work required significant knowledge of a STEM field, then I classified them as working in STEM. Obviously, this was subjective, so consider it a rough estimate.)

Of the people working in STEM who were alive at the time that the article was written, here are the numbers of women:

Only a few magazine issues approached the NSF’s figure of 29% (employed scientists and engineers in the US) or UNICEF’s estimate of 29% (scientific researchers worldwide). The issue with the highest percentage of living STEM women was, once again, National Geographic’s article about fertility rates in Brazil.

If you want to look at the data behind these two graphs, it’s here.

8. Demographic trap

From a panel discussion at a meeting of the National Association of Science Writers in 2001, as reported by Norman Bauman:

Discover’s readership has now reached 40% female, but the other magazines are predominantly male, despite vigorous efforts.

Scientific American has gone from 15% to 25% female. “What’s really maddening,” said [editor-in-chief John] Rennie, is “how abysmally the male-female results will skew along the most stereotypical lines you can imagine.” It’s almost, “If you make it pink the women will like it,” he said.

For example, said Rennie, in reader surveys, an “abysmal” 22% said they were “very interested” in an article on breast cancer. However, 73% women, 16% men were “very interested.” It wasn’t because breast cancer is a female issue — men weren’t interested in prostate cancer either.

This creates a demographic trap. If you make articles more interesting to women, your overwhelmingly male readership declines. About 90% of Discover’s newsstand sales are to men, said [editor-in-chief Stephen] Petranek. “In order to increase newsstand sales, we do more guy-like covers, because the female covers do not do well on the newsstand.”

“It’s funny,” said [Susan] Hassler [editor-in-chief of IEEE Spectrum], whose readership is defined by IEEE’s 94% male membership. “My 13-year-old niece sees this magazine her aunt works on and she goes, ‘Eeeww! It’s geeky.’”

One irony is that many of the editors are women. One reader wrote to Scientific American, “I’ve noticed a decline in your magazine. It seems to correlate precisely with when you started letting women work for you.”

“It’s really ultimately about advertising,” said Petranek. “The intensity of readership is highest among women.” Women feel stronger about a story, and are more likely to clip it and send it to friends. “So we view the female audience for Discover to be extremely powerful. The problem is that the advertising community doesn’t.” You’re a better advertising sell as either a women’s or a men’s magazine, he said.

Scientific American Explorations, which is distributed at science museums, has a 70% female readership, since mothers read it to their children.

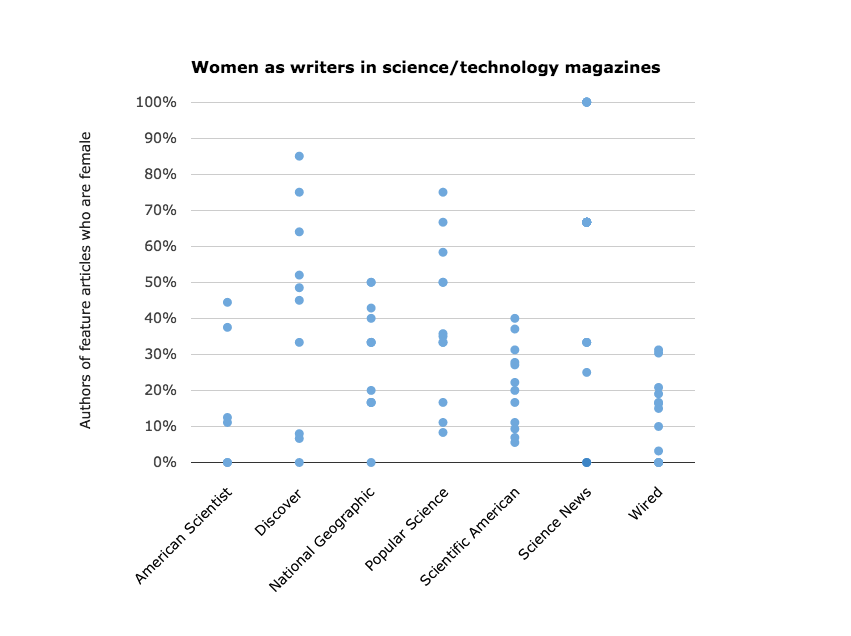

9. Humble data — Women writing in science/technology magazines

When I embarked on this project, I was guessing that some magazines would be good and others bad about including women. I expected that some magazines would hire more male writers who in turn would seek out more male sources. But this was not borne out by the numbers.

I counted the authors of feature articles in each magazine’s issues from 2011. (Unlike counting people mentioned, counting authors was not so time-consuming. I could count all from the year instead of selected months.)

I classified each author as “female”, “male”, or “unknown”, using the same procedure as for people mentioned in articles. If an article had multiple authors, I divided the credit among them in equal fractions.

Although my sample is too small (if not in quantity, then certainly in scope) to perform a meaningful statistical analysis, comparing this graph with the ones above, I don’t see any clear relationship between the percentage of women writers and the percentage of women mentioned.

Each magazine presumably has its own procedure for choosing writers. Some frequently bring in guest journalists while others rely more on staff writers. American Scientist takes a third approach: according to their submission guidelines, “nearly all American Scientist feature articles are written by research scientists about their own peer-reviewed work or work to which they are significant contributors”.

10. More women, less pay

From “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops” by Claire Cain Miller (New York Times, 2016):

Once women start doing a job, “It just doesn’t look like it’s as important to the bottom line or requires as much skill,” said Paula England, a sociology professor at New York University. “Gender bias sneaks into those decisions.”

She is a co-author of one of the most comprehensive studies of the phenomenon, using United States census data from 1950 to 2000, when the share of women increased in many jobs. The study, which she conducted with Asaf Levanon, of the University of Haifa in Israel, and Paul Allison of the University of Pennsylvania, found that when women moved into occupations in large numbers, those jobs began paying less even after controlling for education, work experience, skills, race and geography.

And there was substantial evidence that employers placed a lower value on work done by women. “It’s not that women are always picking lesser things in terms of skill and importance,” Ms. England said. “It’s just that the employers are deciding to pay it less.”

A striking example is to be found in the field of recreation — working in parks or leading camps — which went from predominantly male to female from 1950 to 2000. Median hourly wages in this field declined 57 percentage points, accounting for the change in the value of the dollar, according to a complex formula used by Professor Levanon. The job of ticket agent also went from mainly male to female during this period, and wages dropped 43 percentage points.

The same thing happened when women in large numbers became designers (wages fell 34 percentage points), housekeepers (wages fell 21 percentage points) and biologists (wages fell 18 percentage points). The reverse was true when a job attracted more men. Computer programming, for instance, used to be a relatively menial role done by women. But when male programmers began to outnumber female ones, the job began paying more and gained prestige.

In the 1950s, the percentage of computer programmers who were women was somewhere between 30% and 50%. In the 1960s, with programming jobs starting to require engineering degrees, the percentage of women bottomed out at about 12%. The percentage gradually climbed in the 1970s and 1980s to a peak of about 37% in 1984. Then it fell again to the current level of about 17%. (“What Programming’s Past Reveals About Today’s Gender-Pay Gap” by Rhaina Cohen, The Atlantic, 2016; “When Women Stopped Coding” by Steve Henn, Planet Money, 2014)

One area of science is majority female: social and related scientists are 60% women, with the subdiscipline of psychology at 73% women. People whose college major is psychology or sociology go on to earn a lower median salary than majors in chemistry, computer science, geology, physics, math, or engineering. (“Salary Increase By Major”, Wall Street Journal, 2008)

11. Science/technology compared to other industries

More from “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops” by Claire Cain Miller (New York Times, 2016):

Of the 30 highest-paying jobs, including chief executive, architect and computer engineer, 26 are male-dominated, according to Labor Department data analyzed by Emily Liner, the author of the Third Way report. Of the 30 lowest-paying ones, including food server, housekeeper and child-care worker, 23 are female dominated.

(Female “dominated”?)

How does the workplace discrimination in majority-male science/technology jobs compare to the discrimination in majority-female science/technology jobs? How do these compare to the discrimination in other industries?

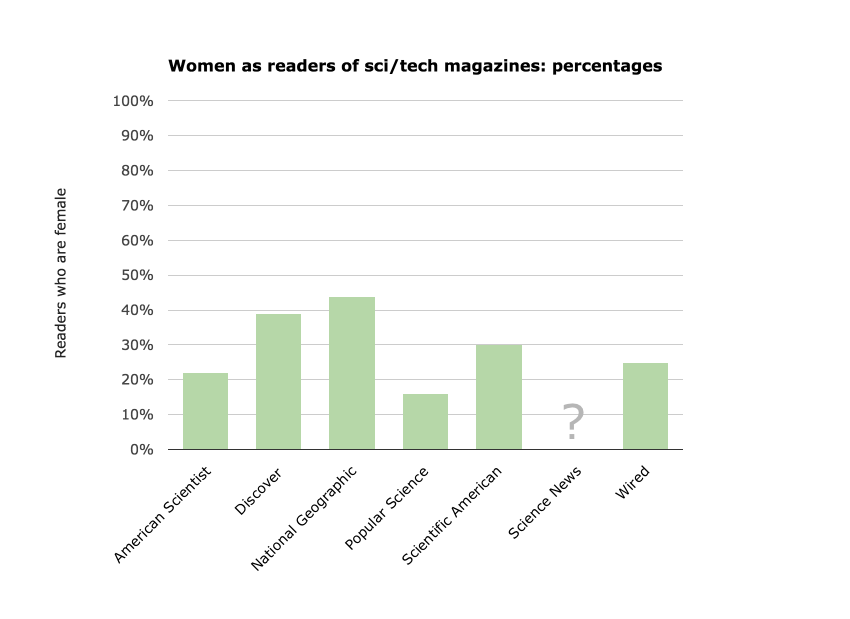

12. Humble data — Women reading science/technology magazines

The following graphs are based on information from each magazine’s media kit.

(Science News was the only magazine that didn’t provide their media kit publicly. I submitted a request through their contact form but got no response.)

I notice a similarity between the first graph above (“Women as readers of sci/tech magazines: percentages”) and the graph in an earlier section showing “Women & girls in science/technology magazines”. Is there a relationship between the number of women reading a science/technology magazine and the number of women that the magazine writes about?

13. Circulation is replaced by reach and engagement

From “Post-linear journalism: Why the media needs to rethink the story” by Jussi Pullinen (2017)

As the focus switches from distributing products to distributing single stories, the measures for impact also change.

Circulation is replaced by reach and engagement – both things that were difficult to measure before.

Reach is about awareness.

On social media reach tells you how many people saw your stories in their feeds. It’s how many people opened a newsletter containing links to your stories. Reach is a measure of your passive audience – the people aware about you but not yet engaged.

As we’ve seen, to many newsrooms this audience used to be automatic.

But in a post-linear environment it needs to be constructed again and again, basically around each individual story. This is why distribution of journalism has become a central part of the job for digital newsrooms.

This is why sharing, tweeting and sending push notifications matter. It’s why real-time analytics matter: you can tell if people are even becoming aware of the existence of a story or not.

Engagement, on the other hand, is about active readers.

Measuring engagement has many phases, beginning with the portion of the passive audience that becomes a reader. Clicks.

Clicks are often dismissed as an irrelevant measure for newsrooms, but this is mistaken: converting a passive audience to an active one is key in achieving impact, and clicks are a decent measure for this.

As a measure, clicks also are the closest thing to circulation: they are an approximation of the active audience but do not alone explain much of what or why the audience actually does.

Time spent on an article is a much better measurement for what the audience actually wants or does.

For a product, the times a person returns in a week or month is also relevant. Understanding how users navigate within the product is also important.

But the main point is that the more non-linear the media environment becomes, the less automatic the audience is.

When science/technology magazines can count less on having a stable audience of subscribers and must count more on constructing an audience around each individual story, how does that affect the gender distribution of writers, sources, and readers?

14. Defining what is important

From A Place in the News by Kay Mills (1988):

Women had not been in the news because they had not been performing tasks or living lives that men considered important. Women had comparatively little role in defining what was important and therefore what was news.

From How to Suppress Women’s Writing by Joanna Russ (1983):

The Double Standard of Content is perhaps the fundamental weapon in the armory and in a sense the most innocent, for men and women, whites and people of color do have very different experiences of life and one would expect such differences to be reflected in their art. I wish to emphasize here that I am not talking (vis-à-vis sex) about the relatively small area of biology — about this kind of difference in experience, men are often curious and genuinely interested — but about socially-enforced differences. The trick in the double standard of content is to label one set of experiences as more valuable and important than the other.

Russ goes on to quote Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own” (1929):

It is obvious that the values of women differ very often from the values which have been made by the other sex; naturally, this is so. Yet it is the masculine values that prevail. Speaking crudely, football and sport are “important”; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes “trivial”. And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction. This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battlefield is more important than a scene in a shop — everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists.

15. Her soft features belying her outsize thesis

A smattering of sexist remarks that caught my eye while counting people mentioned in articles…

From “The Future of Light Is the LED” by Dan Koeppel (Wired, September 2011):

Working out of their home in Redwood City, California, Lenk and his wife, Carol, an electrical engineer…

From “If We Only Had Wings” by Nancy Shute (National Geographic, September 2011):

Aerospace engineer Francis Rogallo and his wife invent the flexible “paraglider” wing…

From “Flying on Sunshine” by Alexandra Witze (Science News, September 2011):

That effort, paid for mainly by an entertainment company led by Carl Sagan’s widow…

From “The Hidden Organ in Our Eyes” by Ignacio Provencio (Scientific American, May 2011):

Science is a cruel mistress.

From “It’s Complicated: The Lives of Dolphins & Scientists” by Erik Vance (Discover, September 2011):

In the escalating war over dolphin rights, two pioneers in the study of cetacean consciousness have sacrificed their decades-old friendship for their beliefs… A petite woman with wavy brown hair and piercing green eyes, Mash seems as impassioned about BMAA as Cox himself… Lori Marino, a neuroscientist and cetacean expert at Emory University, kicked things off, her soft features belying her outsize thesis… Kinetic where Marino was calm, her jet-black hair contrasting sharply with Marino’s gentle brown, Reiss spoke in more urgent tones…

16. Pop-cultural imperialist anthropology

I forget where I first read or heard criticisms of National Geographic, but Victor Ray sums it up (Washington Post, 2018):

National Geographic has long offered a kind of pop-cultural imperialist anthropology that centers the white gaze and exoticizes people of color.

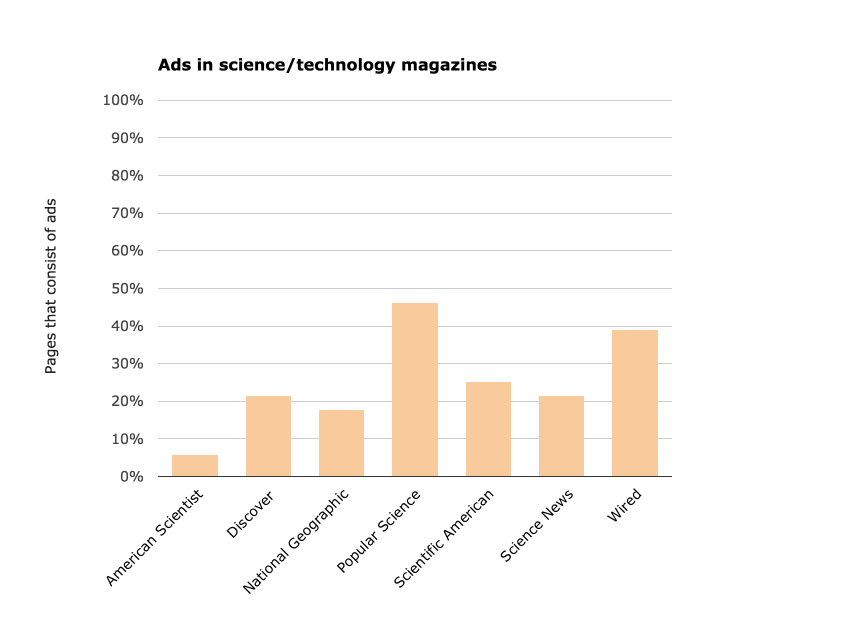

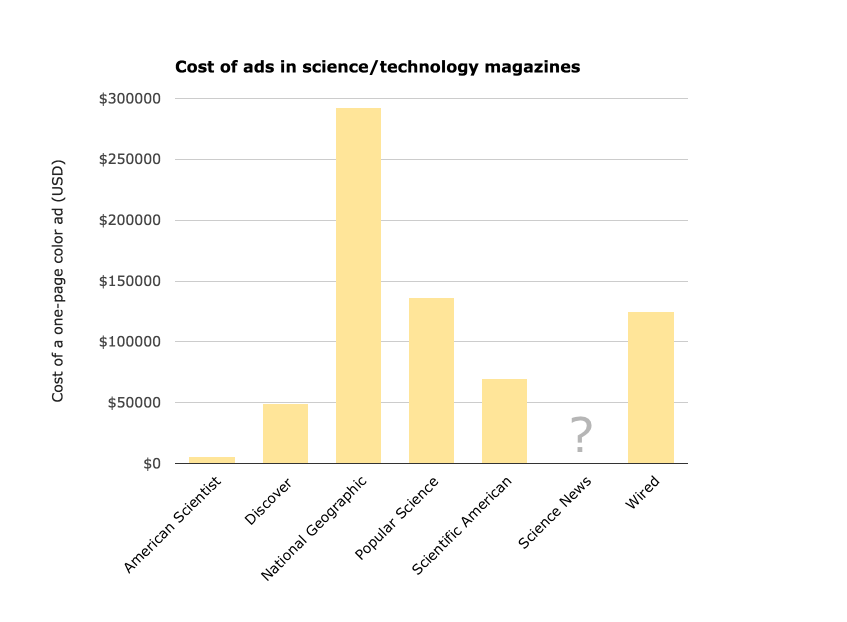

17. Humble data — Advertising in science/technology magazines

Does the amount of advertising in a magazine have anything to do with its (under)representation of women?

In the January 2011 issue of each magazine, I counted the pages that consisted of ads. (I counted by approximate fractions of pages. If ads covered half of a page, I counted that as 1/2 page.)

I also looked up the price of ads in each magazine’s media kit.

If you compare the second graph above (“Cost of ads in science/technology magazines”) to the earlier graph showing “Women as readers of sci/tech magazines: circulation”, it’s obvious that the cost of ads is closely related to circulation.

Comparing the first graph above (“Ads in science/technology magazines”) to the others in this article, I don’t see any clear relationship between the amount of ads in the magazine and the percentage of readers, writers, or people mentioned who are women.

Data behind these graphs: ads and ad rates

18. How more subtly to control the press

From “Sex, Lies & Advertising” by Gloria Steinem in the July/August 1990 issue of Ms.:

About three years ago, as glasnost was beginning and Ms. seemed to be ending I was invited to a press lunch for a Soviet official. He entertained us with anecdotes about new problems of democracy in his country. Local Communist leaders were being criticized in their media for the first time, he explained, and they were angry.

“So I’ll have to ask my American friends,” he finished pointedly, “how more subtly to control the press.” In the silence that followed, I said, “Advertising.”

The reporters laughed, but later, one of them took me aside: How dare I suggest that freedom of the press was limited? How dare I imply that his newsweekly could be influenced by ads?

I explained that I was thinking of advertising’s mediawide influence on most of what we read. Even newsmagazines use “soft” cover stories to sell ads, confuse readers with “advertorials,” and occasionally self-censor on subjects known to be a problem with big advertisers.

19. Advertising in science/technology magazines for kids

In researching this article, although I didn’t collect enough data to include them in my graphs, I looked at a few magazines for kids.

One of these magazines had the third most ads of any magazine that I looked at (behind Popular Science and Wired). The December 2010 / January 2011 issue of National Geographic Kids was 36% ads. That doesn’t even count the two feature articles that were about products (one was about the making of a recent movie, the other was “5 Smart Toys”) and an article about tigers immediately followed by an ad for a video game with a tiger character.

Another kids’ magazine had among the least ads (and among the most interesting articles) of any that I looked at. The January 2011 issue of Muse had 2 pages of ads for educational products at the end, making it about 5% ads.

20. Humanity would be extinguished

From an article called “Women and Political Power” by Luke Owen Pike in the very first issue of Popular Science (May 1872):

There are few subjects interesting to man in which clever women do not sometimes also take an interest; and from this fact it has been hastily inferred that women might, with profit, devote the same attention as men to any and every branch of study. Such an inference leaves out of sight the fact that women rarely look at any subject from the same point of view as men; their opinions often have the value which is to be found in the observations of an intelligent spectator when persons, whose whole attention is absorbed in any pursuit, fail to perceive what most concerns them. The best critic is not always a good author or composer; and excellent suggestions are frequently made by those who are not fitted by Nature to carry their own ideas into operation. This is especially the case with women, who, if they were to devote their whole energies to science or to politics, would do violence to their physical organization. The prolonged effort which is necessary in order to work out any great scheme, to make any great discovery, to colligate any vast mass of materials by a great generalization, is a heavier strain on the vital powers than any merely physical exertion. It is, like military service, inconsistent with that bodily constitution which is adapted to maternity, and all that maternity implies; nor does it seem possible that by any process of selection, either natural or human, this difficulty can be overcome. The change in woman’s nature must (if effected at all) be effected either in one generation or more; if in one, humanity must immediately cease to exist; if in more, humanity would only be extinguished by degrees; but the diversion of woman’s vital powers, from the course which they take by nature, is neither more nor less than the abolition of motherhood. And this, either wholly or in part, either directly or indirectly, is what some earnest men are preaching in the name of sexual equality.

Also:

A state with an hermaphroditic form of government, if even it could exist for a generation, is by Nature doomed to extinction; it may, however, be worth while to consider what kind of being a woman would become who should take an active part in the election of a representative. As an energetic member of his committee she would have to fight the battle, foot by foot, with his opponents of either sex; she could not always sit at home and restrict herself to the use of a voting paper, because she would then tacitly admit her unfitness for political life with all its hard work and its turmoil of speech making; she would be like a foreigner giving a vote from a distance, without a knowledge of the qualities requisite for success in Parliament. It would be necessary for her to be thoroughly prepared for the fray—breeched instead of petticoated, with a voice hoarse from shouting, with her hair cropped close to her head, with her deltoid muscles developed at the expense of her bust, prepared with syllogisms instead of smiles, and more ready to plant a blow than to shed a tear. She hurries from her husbandless, childless hearth to make a speech on the hustings; with hard biceps and harder elbows she forces her way through the election mob; her powerful intellect fully appreciates all the ribald jests and obscene gestures of the British “rough;” she knows the art of conciliating rude natures, and can exchange “chaff” with a foul mouthed costermonger; or, if necessary, she can defend herself, and blacken the eye of a drunken bargee. She has learned all the catechism of politics, and when she mounts the platform she can glibly recite her duty to the world according to the side she has chosen. Experience has taught her the value of invectives, and she denounces her opponents with a choice selection of the strongest epithets; at first she speaks loud in a tone of contentment and self satisfaction; she ends by losing her temper and bawling at the top of her voice. The crowd, never very indulgent, has no mind to respect a sex which makes no claim and has forfeited all right to forbearance. The hardened lines of her face are battered with apples, brick bats, and rotten eggs—the recognized weapons of political warfare. Perhaps the very place where she stands is the mark of a storming party; and, after enjoying the glory of an encounter with a prize fighter (it may be of her own sex), she is at last brought to the ground by superior skill and strength. Then probably she retires to her home; but I, for one, had rather not follow her thither, or into that House of Parliament of which she is destined one day to become an ornament.