If you were to metaphorically represent media depictions of Detroit as photos of individual people, most would be either a mugshot of a scowling black man (the personification of crime lurking among abandoned buildings) or a photo looking down on big sad brown eyes like one of those “save the children” ads (the personification of neediness and white man’s burden).

The Allied Media Conference, held in Detroit for more than half of its 18 years, generates a powerful counter-narrative and counter-imagery about Detroit. The AMC is very much by and about Detroit (about a third of its participants are from Detroit). It’s also a place for wider communities of people of color, queer and trans, disabled, low-income, and other identities and issues, to come together and organize around common principles. At the AMC for the first time this year, I was amazed and humbled by the incredible work that’s being done by people at this conference and in Detroit. (AMC principle: “Wherever there is a problem, there are already people acting on the problem in some fashion. Understanding those actions is the starting point for developing effective strategies to resolve the problem, so we focus on the solutions, not the problems.”)

Here are some images that I want to share from the AMC — that, I hope, will give you a better sense of it than I can describe in words.

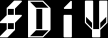

Poonam Whabi and Kwesi Ferebee of Design Action Collective gave a presentation called Poster Power: Toolkit for the Design Activist. Poonam designed the poster above (and gave me permission to use it here). Kwesi and Poonam taught about design principles like having a visual hierarchy, about really considering the audience for whom the poster is intended, and about choosing to make the poster either angering or empowering depending on the situation. I thought this poster was a beautiful example of empowering. (AMC principle: “We emphasize our own power and legitimacy.”)

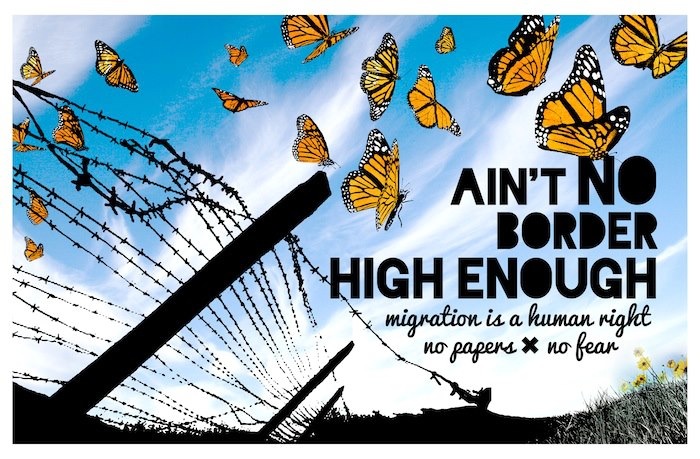

In a presentation called Two-Spirit: Then and Now, Harlan Pruden showed this image of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. It was one of many boarding schools for Native American children operating in the 1800s and 1900s. Its goal was to erase the culture, language, and religion of children’s various tribes from their minds. In this photo, Harlan pointed out the fourth girl from the left in the front row. With her arms crossed and her face defiant, it’s like she’s saying, “You can make me go to this school, but you can’t break me.”

This photo and the next one are from a bus tour of Detroit called From Growing Our Economy to Growing Our Souls, led by Richard Feldman of the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center. I hesitated to include this photo because I don’t want to play into the stereotypical imagery of Detroit’s abandoned buildings (disaster porn). I’ve cropped out the gaping orifices of the building, which is the old Packard Plant, to focus on a sign that was posted by the property developer who plans to gentrify the area. It reads: “No trespassing / property is privately owned / for the safety of the community / do not enter / violators will be prosecuted”. Notice the incongruous use of the word “community”.

On the tour, Richard taught about Detroit’s community gardens, community art, and the community-focused James and Grace Lee Boggs School. (AMC principle: “Place is important. For the AMC, Detroit is important as a source of innovative, collaborative, low-resource solutions.”) Detroit’s sense of community doesn’t come from gentrification. Like so many of Detroit’s vegetables, it’s locally grown and nurtured.

This photo is from the Heidelberg Project, which is developed by artist Tyree Guyton. As our tour bus pulled up beside the pink Hummer, Richard explained that the Hummer represents Martin Luther King’s “triple evil” of racism, militarism, and materialism. Racism, because of actions by the auto industry and the government — like eminent domain kicking out residents to build highways and a new GM plant — that favor white folks over black and brown folks. (I’m not sure I remembered that symbolism correctly, so don’t quote me on it.) Militarism, because the Hummer is used by the military. Materialism, because some people feel they need to drive a Hummer around the suburbs. The Hummer sinking into the ground and the tree growing out of it represent the decline of intertwined racism-militarism-materialism and the growth of new economic systems that are better for the environment and the human soul.

I promised 4 images, but guess what, there’s a bonus. The “Detroit” sculpture at the top of this page (photo colors altered) was made by CAN Art Handworks, the final stop on the tour. A couple days earlier, at a performance of The Secret Society of Twisted Storytellers, I happened to hear the owner of CAN Art Handworks, Carl Neilbock, tell his interesting and funny story of growing up a mixed-race child in post-Nazi reconstruction-era Germany, coming to Detroit to find his father, and deciding he wanted to stay.

I heard many stories on this trip, at the AMC and beyond. The stories told to me by Detroiters about Detroit, by people of color about people of color, and by queer folks about queer folks, challenged and contradicted the narratives that people not of those groups, people with louder voices in our society, have imposed on them. Many of these stories were new to me. As a white person who’s been working for the past 5 years to recover from the racist beliefs and practices I’d accumulated and been in denial about over the previous 20-something years, the AMC was a reality check about how much work I still have to do. Even as a genderqueer person, the AMC was a reminder that I’m not used to spending time among communities of queer and trans folks. I still have a lot to learn as I try to contribute constructively to social justice, but the AMC provided stories to get me started and tools to help me continue. (AMC principle: We begin by listening.)